in person interview, Dallas, Tx March 27, 2022 at 8am

Stephen: I want to say one thing right off: I did not want to be one of these old people who’s always talking about how good things used to be. You see that happening, and I see it happening already in myself. I was about to say, “Oh well, everything was so much better in the 60s,” and I shouldn’t say that. I should just say that it was different.

David: Right. Absolutely.

Because there are many good things about it now, and we were [in Santa Fe] not too long ago—a year ago last fall—and we really enjoyed the city. That area around the railyard has developed…

I used to work at a bookstore there. Big Star Books is what it’s called now. It used to be Blue Moon back in the day. It’s a little house on Guadalupe, right at the railyard there.

Yeah, yeah. That’s a wonderful area. I went to St John’s, and we walked up there, rode up there…and they have a hiking trail now.

I used to do the trail back there: Atalaya Mountain. Is that the one that’s there?

Yeah, it starts right there. You can get there right by the campus.

Yeah, there’s a little parking spot.

When I was in school, there was no such thing. In fact, when I was there in the 60s, the idea of hiking hadn’t really become as popular as it is now. You could get wild and go off into the hills, and come back, and now, it’s like “Oh, let’s hike.” It’s an official thing. “Let’s all do it together.”

You have your gear, and you have to look and dress the part. I used to do a lot of cycling before those mountains destroyed my knees, and it’s always funny to me to see the guy on the $7,000 bicycle with the spandex on, and I go up the mountain faster than him.

[Laughs].

Just because you look the part doesn’t mean you can do it!

There’s a wonderful book called A Walk In The Woods by Bill Bryson, that was made into a movie. Are you familiar with the story?

I know the basics from working in bookstores, but I never actually read it. But it was really popular for a long time.

Well, it’s a great read, a very entertaining read. And one of the main themes he explores in the book is that very thing you’re talking about. They encounter a lady who was so preoccupied with getting all of her gear right, and she’s having trouble with her gear, and it just goes on and on and on. And they just what to walk. At least Bill just wants to walk.

I climbed Wheeler Peak on my 36th birthday outside of Taos, in a t-shirt and shorts, and [with] a very basic backpack. You don’t need anything. You just put one foot in front of the other, and eventually you amble somewhere. You might not get anywhere, but you go somewhere. You have your experience, and you come back.

Yeah. This is almost like the people that we see at the gym now. So many have the fitness monitors and the electronic gear that tells them just how hard they’re working. [Laughs]. Well, I would think I would know that! But I’ve got to try to not be judgmental about this, because we live in a technological age, and people are very fond of their equipment, and they enjoy using it.

Oh, I have backpack full of equipment! On my bicycle I had a little computer for a little while that would tell you how fast you were going, and the distance you traveled. One day I took it off and realized I enjoyed bicycling a lot more.

[Laughs]. Well, I’m kinda unique in the gym—and unique everywhere I go, I guess. I love to read while I work out, and I always select books that are maybe short essays or poetry or little brief things that I can read a few and then do a set, and then go back and read a few more. So I’m carrying little books around with me in the gym, and the 30 or 40 people that are there look at me, and they’ve all got their smartphones.

Right, blasting their playlists of whatever the workout mix of the day is.

And if I can read, I can get my mind off what I’m doing. And the time really just goes by, and I get a good workout.

Absolutely.

Because I’m putting more into it and spending more time there. But we’re just all different in that way, and I’ve seen Hal [Stephen’s partner], who loves gadgets and gear, go through a lot of phases. And, of course, the people who make all this crap, they want you to keep going through these phases! [Laughs].

The worst job I ever had I was doing telephone technical support for Apple.

[Whispered] Oh, gosh…

I didn’t work for Apple, I worked for another company. It was a contract thing, a terrible job. Most people were fine, they were just like “Hey, something’s broken, I need help,” or whatever, but then you’d get the people who are convinced they can’t live for two seconds without their iPhone, and they just start screaming and yelling and I’m like, “Bro, come on. I’m not getting paid nearly enough to deal with you…”

[Laughs].

“…and if you shut up for 2 seconds, I’ll solve your problem.”

You have a varied background, it sounds like, David.

Brutal.

Brutal? [Laughs].

I have a music degree, which is worthless when it comes to getting a job. I learned a lot and I’m glad I did it, but when you go start applying for jobs, people are like “Oh, music degree.” They think it’s easy, for some reason, to get one of these things, and I’m like “You just take your business degree and add 40 hours a week of practicing on top of that, and then we’ll talk about how easy it is or not to get one of these things.”

Good point.

And that’s fair. That’s their loss, not mine. But I definitely have done a lot of things. I did technical support. I owned a bakery for a while.

You owned a bakery?

Yeah, for about four years.

Sweets?

Mostly sweets. My real interest was more in the bread side of things, but you sell the sweets; the bread doesn’t sell as well. The markups are better on cakes and whatnot. But [it was] all-natural stuff, mostly local. No food colorings, none of this b.s. None of that fondant crap.

[Laughs].

Fondant was developed as a food preservative originally in the 1700s, because you sealed a cake in it and it’s airtight, for all intents and purposes. You were supposed to lift it up, slice your cake, and put it back down again. It was the Saran Wrap of its day.

Ahhh…

You were never supposed to eat it. I went to the Nasher Sculpture Center [in Dallas] yesterday and someone was setting up for a wedding in the little courtyard, and they had a very traditional wedding cake, this multi-tiered fondant-covered crap. What is the point of this? Nobody’s gonna eat it, and if they do eat it, it doesn’t taste good. But it looks right. And this is America, and what else matters?

So, the bakery is one of the things you’ve done, and now you are in South Carolina teaching?

I’m in North Carolina. I did the tech support job until July of last year. I did it for just under two years, and they gave me a promotion, and I went through the training for this promotion, and then I politely told them to go fuck themselves, because basically they were adding thirty to forty hours of work a week on top of the forty hours I was already doing, and they weren’t paying really well for that. And you still had to do it all in forty hours, so I was taking on a lot of stress for basically nothing. The company’s name was Conduit, and they were the business services division of Xerox. And they just treat their people really badly, at least on the Apple side of things; I have no idea what it’s like on the other side of the company. So, I quit, and I ended up working at a small company. There’s only four of us who work there, and we build websites with universities to study and educate about different medical problems. So, the main project I was hired for is building a website to teach people in the early stages of dementia and memory problems and their caregivers about the financial and legal things that they need to do. And this is in conjunction with the University of California system.

It sounds like something that would do good.

It’s good. I’m not wasting my time trying to sell some widget that nobody needs, and theoretically, this stuff makes a big difference in people’s lives, so it’s nice. And they treat me like I’m a human.

You go into an office, or do you do it at home?

I go to the office, but they’d let me work from home. Two of the four of us work from home, still. Part of the office is a little house in Durham, and the other half of the office is rented out to this company that does psychiatric telemedicine for people in prisons.

I can imagine. Jeez.

But it’s a very small office. Everybody’s vaccinated. They’re working in prisons, and we work in public health, so everybody has to be vaccinated, so I feel relatively safe there. And I have my own office. I can close the door. There are cherry trees outside the windows. It’s really nice, actually.

Is this a place where you see yourself being for a little while? A few years?

Yeah, hopefully. Because searching for jobs just sucks, and finding a place that actually treats you well is so rare at this point, that I’m quite happy to stay there forever.

I just don’t understand it, David, I don’t understand why we feel that we have to wring people to get every last bit of juice out of them. Think of Amazon: the way [workers] are treated in their processing facilities. As I was telling Hal the other day, when I became a librarian in 1980, before computers, we didn’t have any sense of quantification. There weren’t any attempts to measure output. There was a good faith belief that if we cared about people and our work, and if we were intellectually curious, we would answer questions well, and take the time needed to do so. We’d show people where to get the information that they wanted. And then by the time I left it had gotten down to where they were counting how many times the books had been checked out. They were counting how much time we spent answering questions, and blah, blah, blah.

My first job as a teenager was shelving books in a library. I loved it. $5.93 an hour to shelve books.

[Laughs].

But when you’re 16, it’s great. It was fine: gas was a dollar a gallon, and you could get a pack of smokes for a dollar. Not that I smoke anymore, but…

This was another change before I retired in 2005: they began requiring that the librarians to shelve the books, there were no more pages. [The idea was] librarians shouldn’t be spending that much time otherwise, since book ordering had been automated, you know?

The only time I applied for grad school was in my thirties, when I applied for a Library Sciences program at UNC Chapel Hill, and they were smart enough not to accept me.

[Laughs].

Which worked out better, because the job I have now pays better than library jobs in my area. Not by a lot, but library jobs just don’t pay very well.

So, tell me how you got into music. We’ve been talking about baking and everything else…

In fourth grade I started playing flute. The elementary school band director came around and showed us all the instruments, and nobody told me you had to buzz your lips to play a trumpet. With flute, I could make a sound. It was like blowing over a Coke bottle, just the basic physics of it. I did that for a few years. And in sixth grade I wasn’t really feeling flute anymore. And I hated the middle school band director. The guy was awful. His name was Richard House and, needless to say, we all called him “Dick House.”

[Laughs].

As an adult, obviously, I have lots of friends who have music degrees who have started teaching, and I understand that just because you end up there doesn’t mean you should be there, necessarily. Then in 7th grade they started a Beginning Strings class, and I thought, “Well, I want to keep playing music, so maybe I’ll do this instead of flute.” And because I was the tall mongoloid, they gave me a bass, and that was basically that. At this point I play mostly free improvised stuff, free jazz, some modern classical stuff, and that end of the spectrum.

But you’re not in a group, per se.

I lead a group called Polyorchard, which is a flexible ensemble that does all kinds of stuff. We’ve done Terry Riley pieces and John Zorn pieces, and stuff we write. We did Jackson Mac Low, the poet; we did some of his gathas, and then a lot of other free stuff. Actually, I have CDs for you if you want. I can leave you with some.

We can trade CDs. I don’t know whether you have any of Jerry’s CDs

The only CD I think I have is Ground, with the stickers on it. I love it. The stickers were actually the reason I pulled that out of this batch of CDs. “This is small press weirdness, so I’m definitely gonna get this.”

[Laughs].

[The ritual exchanging of CDs.]

Take any of those [Ground, Haramond Plane, Lattice, and Song Drapes] that you care for. These are all extras that I’ve accumulated over the years. Interesting covers. Polyorchard.

There are different lineups. I play on all of them. This one [Sommian] is bass, viola, two B-flat clarinets, and bass clarinet. This one [sextet|quintet] is a different mix: it’s a quintet and a sextet. This one [Ink} is two discs of bass and trombone, which is not as boring as that sounds, hopefully. And this [Black Mountain] is music that we actually wrote and recorded for the 2018 Black Mountain {Re}HAPPENING, and that’s originals by us, intermixed with Jackson Mac Low’s gathas, which are like these crazy poetry grid pieces.

Black Mountain…

That was the one time we were allowed to play the Black Mountain. Now they only have famous people from New York, so I’m not famous anymore.

“Anymore.” Ha!

If I ever was.

Thank you very much [for the CDs].

Thank you, this is great.

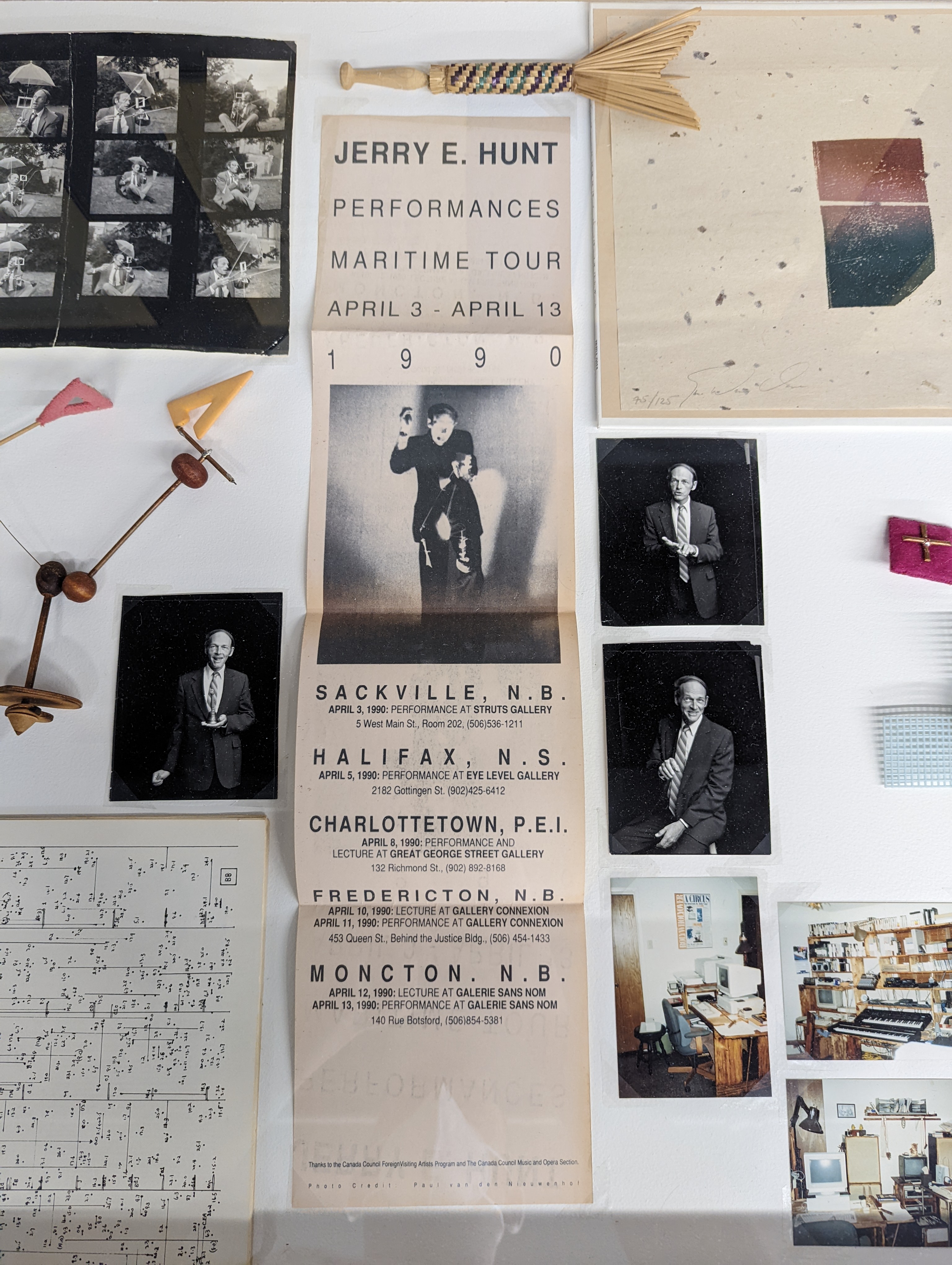

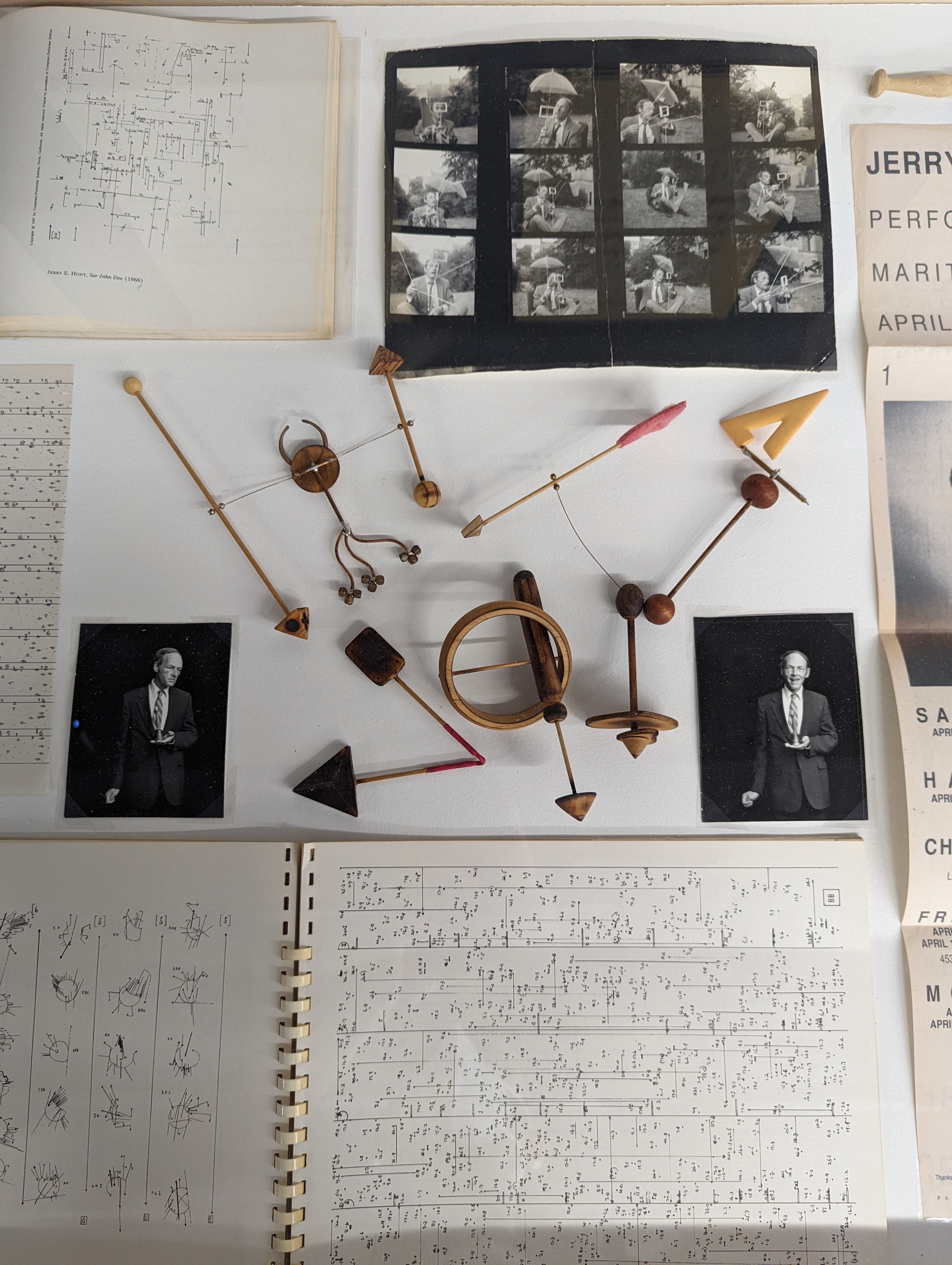

You know the gallery in Brooklyn, Blank Forms, is reissuing Jerry’s LPs.

I’ve ordered the Irida ones, and Ground as well. Pre-ordered; I haven’t gotten them yet. They sent me pdfs of all the books and stuff, but I’m playing in Brooklyn June 4th,the week before it closes. I was gonna go, one way or the other. I play with Eugene Chadbourne, and he got a week at The Stone, so we’re doing the last day at The Stone and a couple days in Brooklyn, but before those days I’m doing a short tour with this Canadian guitarist, and they [Jessica Ackerley] booked some stuff in New England for us. And I told them, wherever we end up on June 3rd,I have to be close enough that I can make it to Brooklyn to go to the Blank Forms exhibit in Brooklyn, before soundcheck at The Stone. This is a must, and they’re only open Thursday through Saturday, so if I don’t go on that Saturday, I’m not going to be able to see it because I’ll be out of town by the following Thursday.

But getting back to the stickers on Ground…you know that was Joseph Celli’s OODiscs [label]. So, when Jerry and I were looking at the first CD that we received, and we saw the errors, our joke between us was “Uh oh, another O-O!”

[Laughs].

Now, do you know about these books?

This one I have [Stephen’s book Partners]. I actually have a copy of this here with me, and this one I have ordered [Blank Forms 08 Transmissions from the Pleroma], but I haven’t gotten it yet.

I’m so impressed with that. These just came last week. These are both advance copies.

I have the pdf of this [Transmissions]. And just looking through the pdf of this, it’s amazing that someone is doing this and taking the time, and that it’s visual, too. Because I feel like Jerry Hunt is like Laurie Anderson to me, in a way, where when you listen to the recordings, you’re only getting ten percent of the experience. I didn’t understand Laurie Anderson at all until I saw her perform live and then I was like, “Wait a minute, this all makes total sense.” And obviously, at this point, I’m never gonna get to see Jerry, so I’m glad that at least some of this stuff is starting to slowly float out, because for all intents and purposes, he doesn’t exist online. There’s jerryhunt.org, and there are two things on YouTube, and that’s it, basically.

Mm-hmm.

Actually, just last week, or the week before, someone uploaded Telephone Calls With The Dead. I think whatever organization was part of that originally were the ones who uploaded it. And it was this huge thing: all of a sudden it was like “Holy crap! There’s new Jerry Hunt for me to watch!”

How did you discover Jerry’s music?

I was working in a bookstore in Santa Fe, and James Brody, who’s an electronic composer who died in a car wreck in 2006, I think, his wife lived out in Santa Fe, and ten years later— this was like 2015, or early 2016—she showed up with all of his CDs, and it was 500 CDs of things like Stockhausen, 20thcentury avant garde stuff. And there was a copy of Ground tucked in there, and Ground is the only one that came home with me from that stash. I mean, I wanted to buy other ones, but I was like “I’m not finding this again ever in the wild. So, I need to take this one.”

So, [it was] a kind of serendipity, in a way.

Yeah.

I really can’t believe that Lawrence Kumpf has done all this. He called me four years ago with the idea that he was gonna do some sort of exhibit tribute to Jerry and his work, and it’s taken that long for it all to come together. And if I had known, when I got that call, that it would turn out to be this big of a deal…I mean, this is all that needs to happen, really. What he’s done here—the materials and the exhibit—it’s everything that needs to happen to really ensure that Jerry’s work will be remembered. And not only that, but people will discover it and enjoy it.

Are there any plans for the future other than this exhibit?

No, the next step will be the materials, the archives will go somewhere. You know, I’m 78, they don’t need to come back to Canton,, so Lawrence plans to work with a library somewhere—he hasn’t picked one yet—who will be willing to take the material, and who will want the material. The idea being that Lawrence will select a place that’s appropriate for it, and everything will go there.

Hopefully it’ll be a place that does the work. I mean, we know how much effort it takes for an archive to become digital and become accessible. I feel like a lot of collections end up in a library, but then there’s no funding to actually do the work, so they sit in boxes on a shelf somewhere.

You’re exactly right.

My interest in Library Sciences was more related to the archiving side of things, and making that stuff more available.

I hope Lawrence will select a place that will be willing to do just what you’re suggesting. Speaking of that esotericism: I’m reading the biography now of Edward Carpenter that was written several years ago and is now out of print. He was a late 1900s, early 20th century lecturer, poet, writer, promoter of antivivisection, and in this biography, [author Sheila Rowbotham] talks about the enthusiasm at that time, in the late 1800s, early 1900s, for other worlds, for reaching out into other realms, and spiritualism and all that kind of thing. And it was very, very intense, and a lot of it was centered in Cambridge.

Yeah, England was a huge center for this stuff. Cambridge, in particular.

I’ll just bet there’s a lot there.

Even Duke, in Durham, in the 1960s, had the Rhine Institute. They were doing studies in ESP and all this stuff under the auspices of Duke University. It was an official thing, and then Dr. Rhine went and falsified some data, and they got kicked out. The Rhine Institute still exists in Durham, but they’re barely functional; even before Covid, they were barely functional. And I’m somewhat interested in this, but not nearly to the extent that my ex was. I sent her an article recently that I came across about spiritualism in Jews in England after WW1, and their attempts to contact the dead, but through the Jewish culture, which is something that never gets talked about. The article was actually co-written with a rabbi, and totally fascinating. They have pictures, supposedly, of, like, ectoplasm and stuff popping out of people…

Something happened years ago at the library that I’ve never forgotten. There was a magazine—we read so many magazines, of course, to select our books. Part of my job, and a very pleasant part of it, was to read a lot of magazines and newspapers and look for reviews. Anyway, this one magazine had a picture that was really a work of art, meant to be. It was a man lying in a bed, which apparently was in a ward somewhere, and it was the moment of his death. And there was an attempt to represent what his spirit might have looked like as it left his body, and headed to a window in that room, and began to make its way into space. Just, “he’s leaving,” was the sense of it. And I thought, “this is really interesting.” And one the ladies who worked in the department happened to be walking by, and I said “Look at this picture.” And I showed it to her, and she just burst into tears!

Wow.

It was so vivid to her, and somehow it churned her beliefs and her expectations and her hopes and her memories, and it all just came to the fore. And I thought: don’t ever underestimate the potency of little things that you think up, which for you are jokes, in a way. For her, it was just a revelation, and she just walked away, and I thought “Wow.” [Laughs].

Did you ever talk to her about it afterwards?

No, I couldn’t.

Fair enough. Just curious if she ever brought it up.

No.

Because I’d wanna know what happened afterwards, after having a moment like that.

You know, I don’t know why I didn’t. Maybe I had to be on the desk, probably! [Laughs]. She was a delightful lady, and I think I’ve known others in my life like that…. Be careful, because sometimes you’re playing with fire, and for you, they’re fireworks, but for them, they’re bombs.

Oh, absolutely. You can blow up somebody’s life without even realizing it.

Mm-hmm.

It’s really easy. Especially with something casual, something like spiritualism that could really upend somebody’s religious beliefs.

Mm-hmm.

Because, definitely, the way Christianity is practiced in America, it’s really closed at this point, and some people can handle the outside information and some people just can’t. And for some people, it blows everything up.

We live in a part of the area—Rowlett, Garland and Rockwall—which is rather conservative. There are a lot of churches here and a lot of very religious people.

I noticed.

I see it at the gym, and I see the shirts that people wear—the men as well as the women—with their religious insignia. And you know, I’m also familiar with a lot of areas in Dallas that are more occupied by younger people, and you don’t see so much of that there, you know? I think among the young people, unless they’re evangelical, there’s not a lot of interest in religion.

Or at least to not to be so explicit.

Right, right. And I kind of enjoy going back and forth, you know? I like being in the West Village or Mockingbird Station, or Trinity Groves, and being with that group of people, and then I like kinda being out here, because these are very good, kind people, you know? I feel like all of our neighbors, and the people that we encounter in the restaurants we go to…I’m comfortable. But you definitely sense that you are shifting frequencies or, I don’t know how to describe it. Wavelengths or whatever.

There’s definitely an energy transference. Some people are hip to that, and some people can’t handle it at all. It’s really interesting to see how, just like you walking into the room…I’m not a gay man, so I don’t understand what that’s like, but it’s just fascinating to see people react to these things. Or you see an interracial couple walk in or something. You know, it’s 2022, a lot people don’t give a crap, but there are some people who react really hard to it.

[Laughs]. Yes. Well, Hal was born in Germany. His father was a black man, and his mother was a German lady. He was in an orphanage, put up for adoption and then he was adopted by a black family in San Antonio. So, he’s German-born. [He] spoke German in his early years, moved to San Antonio to a black community—he’s mixed race, you could say—and things happen all the time with…we were walking into a shoe store the other day, and a lady came up to him and she said “Oh, where’d you get that tan? I’d love to have a tan like that!” [Laughs]. And it just rolls right off him. He’s utterly indifferent to it. But it hits me, you know? [Laughs].

That’s so funny [that] people even feel like that’s okay to even say. I have black women friends, and people are always commenting on their hair, or whatever. And how inappropriate it is that people just come up and touch them. I would never touch a stranger without asking.

[Laughs]. Well, do you want to go see some places?

We can, or we can talk. Whatever is fine. I actually have like ten more hours of driving today, so I’m good till maybe 11 or so. Another hour and half?

That’s good for me, because we’re gonna be going for lunch later. I owe Hal a good lunch after yesterday. We had a sad experience yesterday. A former co-worker of mine, in fact my boss for over 20 years, she’s had Alzheimer’s.

Oh, no.

So, we took some charcuterie to her husband who’s looking after her. And we couldn’t see her, and that’s ok. I didn’t want particularly want to see her. So, we visited with him at the door, and it was a hard thing. And Hal was with me through it, so there needs to be a little bit of a payback today for him. [Laughs].

That’s nice of you.

Well, she was a wonderful lady. Probably the smartest person I’ve ever known, and one of the best. A good, good person, and as far as a boss goes: totally fair. I mean, the woman just wrote the book on equitability.

It’s amazing to have people like that, because so many people just aren’t, for whatever reason.

I know.

Whether they’re teachers or bosses or whatever. I definitely had teachers who I didn’t get along with, and they couldn’t separate that from the grading. I’m like “My work’s good! I know you hate me, but that’s besides the point!” [Laughs].

Well, what I propose that we do is I’ll take you, and I’ll do the driving, over to the neighborhood where Jerry and I grew up, where we met. And the reason I want you to see that is so that you can see kind of where he came from. And seeing it is more vivid than reading about it.

Absolutely. Even though I know everything’s changed in the intervening years.

But not that much. You’d be surprised. There’s still much you can see that’s very much the way it was when we were prowling around as kids. And then we can talk, of course, as we do the drive.

I love your dogs. They’re great.

Yeah, Coco’s a sweet dog. Coco is a more primitive animal than Meela, she’s a little slower to pick up on what’s going on. She’s very, very loving, but Meela is so smart, and she’s got to be right in the middle of what’s happening. In fact, she’d like to direct! [Laughs].

[Laughs].

Let me make a trip to the john and then we’ll head out. Where are you aiming for, to be tonight?

I’m going to end up in Littlefield, which is between Lubbock and Clovis. But I’ve to go to Austin and pick somebody up and bring her out there, so I’m going down and then going back up again.

I always think of it as “getting” to go to Austin. I love Austin.

I’ve actually never been there. This is actually the first time I’ve ever been to Texas, other than driving across the panhandle on the interstate.

Oh, I wish you had more time to explore Austin, but I know you’ve got duties.

Yeah, maybe on the way back I’ll have a little time.

Hal: So you must enjoy driving.

Yeah, it’s OK. Because of Covid, of course, I basically haven’t gone anywhere in two years, so it’s just nice to be out and about on a trip. But, you know, sitting in a car is still sitting in a car, regardless of how much you like it or what you’re looking at.

Hal: I like to ride. I lived in Austin, too, and I never could get a job there after I got out of the army, no matter how much I tried. But I’d always go down there. And I hated driving, so I’d rent maybe a Lincoln—I never got into anything exotic—but I’d rent maybe a Lincoln, or a Jeep or something, to make the drive more exciting. I hate driving. I may be worse at it now…

It’s the European in you! My dad’s Belgian. I mean, he drives all the time, but I think he’s the same way. I think if he could not have a car…honestly if I could not have a car, I’d be quite happy. But our society is definitely not built for public transportation. Especially driving around this area, it’s clear nobody walks around here. I mean, I really would like to talk to whoever designed the roads. I have some questions. I’ll be polite, but I have some questions!

Hal: We all have six or seven cars around here.

I play bass, so I have to have a car anyway, because you have to have something to carry this thing around. There’s actually a bass in the car out front.

Hal [to dog] You’re just too affectionate.

Honestly, I’m gonna steal this little guy. [To dog] You’re gonna come home with me. [To Hal] If he’s missing later on, don’t be too concerned.

Hal: Well, he [Stephen] told you the story about her, right?

No.

Hal: We got her from the neighbors back here. They have a habit of getting a dog and then just throwing it in the backyard.

Oh, those people. I know those kinds of people.

Hal: They get them, and they just dump them outside the gate, and they did that with her. I took her back and they looked at me like I was an idiot, and then they put her out again, so we rescued her.

People who treat animals poorly…I don’t believe in the death penalty, but I fully believe for people who treat animals bad, or who treat kids bad…

She likes you!

Yeah! All dogs like me, because they’re dogs. It’s not their fault, they don’t know any better.

[Laughs].

Look at them! They bonded. We’ll be back before you know it, Hal.

Hal: OK. Have a nice ride.

Nice to meet you.

Hal: Same here. Be safe and enjoy Austin!

Yeah, I’m looking forward to it.

Bye Coco, bye Meela. I’ll see you later. You stay with Hal.

I’m looking forward to seeing the stars again. You can’t see the stars on the east coast.

There are plenty of places here, particularly out where you’re going.

I had trouble, actually, driving through Alabama. I was doing it in the evening, and I was looking up at the stars and I kept running off the road!

Well, that’s my problem with driving, you know. And I’ll warn you, because I do look at the scenery when I probably shouldn’t be. Hal just fascinates me. He’s creative in ways that I would never expect, and he does these little things around the property, and he’s got this little village started here.

Oh, this is great!

It’s like everything else here: it’s a work in progress, you know? It will evolve, and at some point, it might just disappear.

Well, that’s how it should be.

Look at the little bridges, and the ramps

Like a little pyramid here in the back, and the temple or whatever.

It’s just beautiful. That’s what [Hal] enjoys doing, you know? I love playing the piano, I love reading; he’s working with his hands. He’s doing stuff. He’s arranging stuff.

Yeah, you’re working with your hands, too. Just in a different way.

I guess!

I mean, you’re not using a saw. Unless you’re doing like a Fluxus piece or something.

[Laughs].

I’m really into Ben Patterson. Aside from the fact that he’s the only bassist in Fluxus, he was also the only African American person in Fluxus. There’s a great picture of him and Wolf Vostell, and a couple other guys, sawing this piano in half. It just looks so good. We have the same car. You’ve got a fancier one than me.

How long have you had yours?

This is a 2017 that I bought a year and half ago, but before that, I had a 2005. Same car. Somebody had leased it. They put their 12,000 miles on it for three years, and I bought it right after that. Thank you for driving, by the way.

Oh, sure. They’re great cars. The only problem was this car: they had the idea that they could save gas mileage, and they could advertise a lower gas mileage figure, by putting on a feature that stops the motor every time you stop.

Oh, no, I hate that. My car doesn’t do that. I rented a car once that did that. And every time I thought there was something wrong. And like, do I have to restart the engine at every stoplight? What’s going on?

Right. Well, they’ve made it easier to remove it. They put an icon here now that you can just press and make it go away.

Oh, that’s nice.

But you have to deal with it all the time. Every time I get in the car, every time I start the car, I’ve got to press that icon. So, I talked to the people at the dealership. I said, “Does anybody like this?” and they said no. He said, “We get hundreds of complaints a day.”

It’s a thing on paper to say that it’s better. But it’s not, because it makes everybody’s life worse. Mine is classified in California as a partial zero emission vehicle, because it’s designed to coast, so when you take your foot off the brake, instead of slowing down, it just kind of coasts like when you’re on the highway, which is kind of nice. Because, technically speaking, for those few seconds, it’s not burning [more] gasoline. And it’s just this accounting thing for California to meet their carbon goals. But I’m still putting out the carbon. It’s still happening, regardless of what your paper says! [Laughs].

The latest thing, at least latest for me, they’re prohibiting all-natural gas in a lot of cities now. New homes cannot have gas ranges. And you know, Jerry always said that cooking with gas was the best way to cook, because you had the instant control of the heat.

I don’t disagree, as somebody who’s cooked a lot, but at the same time, it’s so inefficient. It’s only like 25% efficiency, or something like that. So basically, 75% of what you’re burning goes nowhere.

Did you know that the gas stoves leak even when they’re off?

Yeah, I heard about that. And the way we get gas at this point, with fracking and stuff, is so nasty. My apartment has a glass-top electric range, which is okay. I’m okay with this, versus fracking the environment so I could have a gas stove. But it’s definitely a different experience. I prefer cooking on gas.

Well, [Jerry] taught me everything about good eating. I mean, I’m not a cook. I can do a little cooking now. You’d think, after all these years, I would have learned some things. I’ve got some basic things I like to make. But he explored. He had to know, he had get every kind of cuisine’s cookbook and explore, and learn the spices and the techniques. And we enjoyed so many different kinds of food.

I’ve definitely had that problem over the years. Before I left, I planted some nigella seeds, black cumin. I mean, I can get them at an Indian grocery store, but that’s not something I can go buy at the farmer’s market, for instance. Because nobody’s gonna grow that. But I actually just saw that in Durham, it’s supposed to hit 29 degrees tonight, so hopefully they’ll be okay. I knew coming out here. I just put all my plants outside, and it’s just going to be what it is. And if they die, I’ll just start some new ones.

But I don’t think you’ve got a problem. Unless it’s gonna be really cold for a long time.

Yeah, I think it’ll be okay. Because it’s gonna be one evening dipping down for a couple of hours at the most, and then that’s it.

It’s a steadiness, you know, that really gets the plants.

If it’s 20, maybe it’d be a little more of a concern than 29. And because I’m in the city, it’s usually a degree or two warmer than they say it’s gonna be. I’m a mile east of downtown. So weather-wise, for all intents and purposes, I’m in downtown.

I brought all my plants and put them all back outside. I’ve got about six that winter indoors, and it was such a treat to put them back out. And I felt like they were so glad to be out. You know, they don’t thrive indoors.

No. Even if they can handle the shade, it doesn’t mean they like it. My favorite plant is an apricot tree that I grew from the tree that was in my backyard in Santa Fe. I sprouted a couple of them, and one has managed to survive. It’s five and a half. It’ll be six in October. So, I’m hoping in a year or two, I might actually get fruit out of it.

Well, that’s another thing I remember about Santa Fe. We would walk down to the plaza from the college campus and they would very often be apricot trees in the appropriate time of the year, when we could just casually walk over and reach through the fence and get an apricot or two. They were delicious.

I walked to work there. Maybe a 15-20 minute walk, and I would pass apricots, apples, pears, cherries, figs, grapes. And basically, nobody in that area seemed to be eating them, except for me, so I would just be stealing fruit on the way to and from work.

Well, I had always thought that I would return to Santa Fe. And if I had not met Hal, I probably would have. But we’ve been now several times since then, and I’ve always enjoyed my trips out there. But you know, there’s this thing: you really cannot go back. You can’t go back. And part of my attraction to Santa Fe is my pleasant memories of when I was out there.

Of course.

Which was when I was the age I was when I was out there. And with the outlook I had when I was out there. And all that’s changed now. Even though I might like to go back, I can’t go back.

It’s also an incredibly expensive area to live in at this point.

I know. There was a magazine we picked up this last fall when we were there, and a realtor was interviewed, and she said “Don’t buy anything out here now. Put it on hold,” she said. “The prices are just outrageous.” And she’s talking to prospective residents. “Don’t come!” [Laughs].

It’s the same thing where I live in Durham now. Durham, Raleigh, Chapel Hill, all that area has become unaffordable for basically everybody in the last couple of years. Rents have doubled and tripled in some places. And the housing market is so crazy. There was a house in Raleigh, about a month ago that was listed for under $200,000, which is super rare. 900 people showed up to the open house. And they were all ready to cut each other’s throats.

Yeah, I hear stories like that all the time about property here. As soon as a house is advertised with a price, people begin submitting their bids, and they’re upping the price. They’re adding thousands and thousands of dollars. There’s a nice new bridge. I I learned to swim in the little pool here on the right.

Oh, nice.

…which is about to be torn up. It’s too old and cracked. And it’s past its time. I was probably in the fourth grade when I decided I would do my first dive. And I did! I’m sure I executed a perfectly elegant little sissy dive right to the bottom of the pool, because it was only four feet. [Laughs]. I didn’t think about looking to see what the depth would be.

[Laughs].

They had to take me to the emergency room. I had to have stitches.

Oh, man. You’re lucky. That’s one of those things that, like half a centimeter another way, and you could have had a very different life.

[Laughs]. It’s true.

Kids are so dumb. I mean, fearless, you know. Because they do that stuff all the time and never think twice about it. And you know, 99% of the time, it’s just fine.

Yeah. Well, I guess it’s a good thing that we are that way, because we’d explore, we’d extend ourselves, we’d subject ourselves to challenges, you know. You don’t want to sit safe.

And the childhood body is designed to be rubbery, for lack of a better word.

You’ve heard about little children that fall into freezing water and can survive a long time.

Yeah.

It’s not a disaster, really, for a kid to fall through the ice!

Yeah, it’s very different, especially for older folks.

So, this area where we grew up, we’re kind of getting into it now. Of course, in all these years it has become much busier. The traffic, many, many new homes and developments. I learned to drive down this street. My father took me here to teach me, because there was nothing down there. It was all just pasture. Just countryside. That’s completely changed. He was impatient, though. He was such a good driver. He was a truck driver, and then he became a shipping clerk. So, he was excellent. And I was learning, and slow and awkward. And I felt like I already knew it, because that’s the way I approach everything, you know? Mr. Know-It-All! And it just didn’t work at all. So, I went to my sister who was three years younger, and said “Do you think you could show me to drive?” She’s the one who taught me.

My dad taught me and my older brother to drive on my mom’s car because it was an automatic. My dad drove a pickup truck that was a stick, but he would not teach us to drive stick on the truck. If we bought a car that was a stick, he would teach us to drive stick, and I ended up buying an old Volkswagen and learning to drive stick. And then when my Volkswagen was in the shop because it was old—and that happened not infrequently—I could drive my dad’s truck, because I could drive stick. But my brother couldn’t, and it drove him insane, because he’s older, you know? I was allowed to drive the truck and he wasn’t. I mean, it wasn’t that he wasn’t allowed, it’s just that my dad didn’t want anybody ripping the transmission out of the truck. It makes total sense. [He was] less concerned about the automatic in my mom’s station wagon.

I have a truck in Canton, my farm truck. I used to bring in hay for the animals with it, and will again if I did animals again, but it’s a stick, and I’ve enjoyed it very much. It’s a nice little Nissan truck. And the stick is very satisfying.

It really is.

To learn to use it and use it well, to use it efficiently and smoothly, is very satisfying. It’s a real driving experience, which this is hardly… This isn’t driving, this is just steadying!

But on the other hand, when I drive 1200 miles, it’s nice not to have to pump that clutch all the time. That’s for sure. Like when I was going through Atlanta, Atlanta was basically a parking lot. It was an hour and a half to go 20 miles. And I was really glad I was not having to ride that clutch. You know, start and stop, start and stop, all the way through, that would have been…might be good for my knee, though, to have the exercise while I’m in the car. I don’t know.

Hal is a real car enthusiast. I’m not particularly, but he loves the old cars from the 70s and 80s. He has five vehicles. It’s so embarrassing. [Laughs]. Five vehicles. And his latest acquisition is in 1981 Lincoln Continental.

Oh, wow. That’s a boat.

Oh, it’s like driving in a rolling living room.

Yeah, those are super plush cars.

We had a tornado warning the other night and I texted him and said, “Be sure to get in the hallway if the storm comes your way.” And he started getting into the backseat of the Lincoln to perish in luxury!

[Laughs]. Smart man. I find it amazing that we’re still building cities like this, that just sprawl endlessly. I’m willing to accept that, maybe in the 1950s and 60s, we didn’t know better. But now I feel like we clearly understand the environmental costs of these kinds of things. But we keep doing it. I spent the night with some friends in Dallas—north of Dallas, I have no idea what town they live in. They just moved there a couple of years ago, and we went out to pick up a pizza. And we drove by nothing but new construction. And [my friend] was like “Even two years ago, this was all fields and cows.” But it just keeps pushing farther out into the land, because there’s nothing blocking them here so they can just keep doing it.

You don’t remember the name of the town?

Actually, I can look on my phone.

Well, it’s not important. I just would kind of like to know, I was gonna ask you where you stayed.

It wasn’t far from you, which was convenient. Let’s see. [checks phone]. Carrollton.

Oh, yeah. Well, Carrollton was one of the first white flight areas in Dallas. Plano, McKinney, Carrollton, all those communities north of the city. People were getting out of town. They did not want those buses to come for their kids.

Of course.

But now we’ve gone beyond white flight, and we’re into the gentrification. We’re into the “I’ve got a lot of money and I want my space and I want my mansion,” and the new cities that have come into being with that mentality are Frisco and Flower Mound, and places like that. But I’ve seen the city just leapfrog outward—always outward—and northward. You don’t want to go south.

What do you even do with these giant homes? I see these 3,000, 4,000 square foot homes being built. And just the thought of having to put furniture in it, and then clean it…

…and deal with it.

But I guess if you have that much money, somebody else is cleaning it. But, still. I saw a 5000 square foot home the other day, and I just like freaked out. I live in a tiny apartment. It’s 340 square feet.

And isn’t a pleasure to have just enough?

Yeah. I’d like maybe one more room than I have. But I’m totally okay with it. I couldn’t afford to live in Durham, otherwise. I live on, you know, “the wrong side of the tracks,” so to speak, that’s gentrifying faster than you can blink. And I only ended up there because I could afford it when I was doing a telephone job, which really didn’t pay well at all. And now, if I move, my rent is gonna go up $500, minimum.

Well, this [Ferguson] is the street where I grew up, and when we moved here in the 50s, there was one lane on each side, and this was all grass in the center, and I don’t think my father had any idea that all this space was left so that it could be what it is today. This was the house, right here. My sister and I were there. And you know, again, we had shrubs all along the front. A nice vegetable garden in the back. It’s been transformed. But it doesn’t look particularly bad. I mean, they’re doing a pretty good job with it.

It’s still standing.

I think the neighborhood is holding its own. Some neighborhoods have gone down.

Sure. But they’ll come up if you give them another 20 years. That stuff’s always cyclical.

And I’d wander this way, going to see Jerry, or he’d come over to see me, with shopping baskets. Not one, but two! [Laughs]. We were big into bikes when we were growing up. But we also did so much more walking than kids do now. I mean, I didn’t have a car until I was in college. And you know, I walked everywhere. I didn’t think anything about it. I think mother felt like we were safe, even as children, heading out on our bikes.

Me and my friend Nathan, when we were 13, would do 30-mile bike rides on Saturday. Just bopping around, getting away from the parents, like you’re supposed to do when you’re 13.

Walking bridges, walking along the drain pipe, over gullies, hands out to the side to see if you could do it without falling off.

Poking your head in a sewer, or something ridiculous.

Yeah.

My parents were very restrictive about TV time and stuff. I could spend all day with a book but I never would have been allowed to spend all day Saturday watching TV or something.

Well, my parents were not really that engaged with the way we were growing up. I mean, they’d get involved if there were issues, and they’d praise us when we did well, but it was pretty much hands-off rearing.

Yeah, right. Show up at dinnertime. And that’s it.

Yeah. And that was the case with Jerry’s parents, too, until they suspected he might be gay. And then they got really involved because they were so frightened.

Oh, no. It’s so funny. I mean, I know it’s still a thing for a lot of parents today. But it’s just mind boggling to me. Like, you see the trans bullshit going on in Texas right now, and stuff like that. It’s like, it’s your kid man. You might not like your kids’ decisions or whatever, but they’re still your kid. You should still love them and support them, regardless.

This was Jerry’s house: the second one right there [on San Medina Ave]. And again, it had shrubs all over the front, all along the front of it. And now it’s got little gaudy flowers. His piano was in that front window. So, you see, it was fairly close. We lived fairly close. And we were going back and forth a lot. There were five people in our small home, and just the three in Jerry’s, so I liked being over here because there was so much more space.

Mm-hmm.

The only thing that I think about when I think about my parents that makes me pause was that there was this sense that if you didn’t do the right thing, you’d let [them] down. That’s the way we were guided, you know: “don’t let us down.” So, you’d mess up, and you had let them down, and you’ve felt so bad. I don’t know why we had to be made to feel so bad. You know, just go ahead and whip us and make us sore. And it’s over, you know?

Yeah, that psychological thing is really interesting. And I’m that way to myself, in some ways. I’m better than I used to be, but I’m definitely really hard [on myself]. Like, you don’t need to punish me because I will punish myself just fine. But it’s such a weird thing to do to kids. I mean, I realize too, obviously, in the 21st century, we have a different conception of child rearing than we used to have. And hopefully each generation learns from the mistakes.

Well, if you love your child—really love them—and are patient, and spend time with them, mostly things work out well, don’t you think?

Yeah. I mean, I really think that’s all you’ve got to do. You make sure they have food, you make sure they have clothes, you make sure they go to school on time. And you just say yes. Like when I came home and said I wanted to play bass, my parents said yes. I don’t know what kind of conversations they might have had amongst themselves, but to me, it wasn’t a thing. And in seventh grade, I used a school instrument, and in eighth grade when it became obvious that I was serious about it, they got me, like, a cheap plywood, student bass. But I also understand that that was a not-insignificant financial sacrifice at that time, or at least an unexpected one, if nothing else. I was never worried about going hungry. But I was also aware of the fact that there wasn’t tons of money. My parents are not flashy people. They’ve lived in the same house since 1986.

You had one brother?

One brother, who’s two years older than me. My mom was born in ‘51, in New York, to a Jewish family. They were good parents. I’m sure as a child, I might not have thought that, but as an adult…

You can appreciate them now as you look back. Isn’t that always the way?

Yeah. They did a great job. I have no real complaints, especially compared to my friends. And just the horror stories.

The picture that you’re taking [Bryan Adams High School] will include the classroom that we had our wonderful English class in, Jerry and I, with Mrs. Worsham, the teacher who was beyond burned out. But she was still a good teacher, and yet, sarcastic.

That’s my kind of teacher!

We really appreciated her sarcasm when kids would do or say something stupid. She just really leveled them without them even knowing that she’d done it.

Those were the best teachers, who can just, like, stab you in the heart, and you don’t even realize it’s happened.

They’re redoing all the front. This is completely different from the way it used to be. And I’m glad to see the school is being redone. That was the auditorium in there. That was kind of fancy for us when we first walked in. We thought it was just a real neat place. Jerry and I were both in the orchestra.

What did you play?

I played French horn and violin, and he was a bass player.

Oh, he was a bass player? That’s hilarious. I had no idea he had that disease, also!

Well, I don’t think he took it all that seriously. But the thing is, if you were in orchestra and band, you didn’t have to be in the ROTC. So we placed out.

Good for you guys. Screw the military. I mean, the way that they do that stuff to children, it’s just mind boggling to me. I went to Enloe in Raleigh, which was considered an arts high school, and it’s where the nerds went to school. We had sports teams, but they weren’t any good. But the ROTC was super active there still, and it was just like, come on, guys. Nobody here needs to go die for oil. Or at least wait till they’re 18, you know, before asking?

You know, I agree with you, totally, and more. But I think about how when Hal finished high school in San Antonio, with no particular motivation, with nothing behind him from his parents to encourage him to move forward with school. He didn’t know what he was gonna do, and the army was the best thing at the time.

Oh, absolutely. I know a few people like that, that for whatever reason, they ended up enlisting and it actually gave them the focus they needed to become real human beings, which is great.

My friends got some direction. We’re gonna make our way over to the junior high, which is where Jerry and I met. Sometimes I get turned around over here because these streets are…

I was gonna say, I have no idea where I am! I’m good with geography, in my mind, and, you know, orienting myself to where I am in this whole area around Dallas and stuff, I have no clue where I am, ever. I haven’t been here long enough. It would take me years to start piecing it together.

Do you have a sense of direction?

Yeah, I have a really good sense of direction, generally. Certainly, in the daytime. I know where the sun is. You know, like, that was at my back. So, I need to turn around.

Do you know about the little libraries?

Yes. I love the little libraries.

Look, there’s one right there.

Is it a good one?

It’s cute. They’re everywhere.

But it’s Jodi Picoult. I don’t need Jodi Picoult.

I’ve never found much of interest in them, but I’m just glad they’re there.

I think they’re great. And every now and again, you’ll find something super weird or just unusual. And, you know, there’s nothing wrong with reading Jodi Picoult, if that’s your thing, or James Patterson or whatever. Sometimes I love this trashy stuff. They’re totally entertaining.

We all need to kind of have our breaks.

I don’t know if you’ve ever read Lee Child, but I love his stuff. The Jack Reacher books. You know, they’re mindless entertainment. But I can just disappear into that for hours. I read lots of “serious” stuff or experimental stuff or art stuff or whatever, and as much as I enjoy that stuff, you read two pages, and then you got to put it down and think about it for a while.

It’s good to see these homes are like being looked after. It’s still a pleasant neighborhood

Yeah, it looks really nice. Nice and calm. On a Sunday—it’s Sunday, right?—Sunday morning.

Well, of course, that’s the story here. It’s a good time to be driving around. People are sleeping late.

I wish I could do that.

We get up early. We like the mornings.

Me too. My body’s on East Coast time anyway. So I was up at 5:30 this morning, which is a little earlier than I would have liked. But you know, whatever. I would have settled for 6:30.

I get up at 5:30. That’s my usual wake time. And Hal has to be at work every day at 6. So, he’s definitely an early morning person.

I worked shifts like that for a long time at various jobs.

This is our junior high [W.H. Gaston Middle School]. This is really an important school for me because Jerry and I had our first few years together here and you know, it was okay, but they kept us pretty busy with the schoolwork. But here we were free to play and explore. And it was a junior high, now they call it a middle school.

Yeah, mine was the same. At one point it was junior high. And then it was middle school by the time I was there. [Looking at middle school] Oh, yeah. Classic. With the air conditioners in the windows and everything.

Not very many changes here. I don’t think there have been any updates. But the thing is, they put a lot of portable buildings out now.

Yeah, I can see. They did the same thing where I’m at.

But we had classes in the portable buildings, and didn’t think a thing about it.

I mean, as kids, you never would. You don’t know the difference as kids. It’s just that’s where the class is, that’s where you go.

That’s what you do, right. And we had some good teachers, and we had some lousy teachers. But again, we didn’t think too much about evaluating all of that.

I liked reading your book. I read it a few years ago as a pdf that was available online. And then I got the Blank Forms edition that I reread a couple of weeks ago.

Well, I’m really proud of the fact that they reissued that. I never really thought that that book would be published. It really wasn’t written to be. I’m not a writer. But they felt like it was worth it.

I think it’s actually an essential book; certainly in terms of Jerry Hunt scholarship, there’s no question. But I really appreciated reading something that honest. It’s really difficult to look at yourself and be real about it. And I felt like reading it, I got a really good sense of who you were, and who Jerry was, at least at the time. Too many times, you read these autobiographies, and they’re inflated, you know. Or there’s a point of view that they’re trying to sell. But there’s no point of view [in your book]. It’s just like, “This is how it was.”

Well, I’m glad to hear you say that. And I think that that’s pretty much true. Pretty much.

“Pretty much.”

[Laughs].

Of course, there’s always a little ego involved.

Yeah.

And that’s okay. You need a little ego to tell you to do it in the first place.

But you know, even in addition to that, I don’t think any of us is able to know what really happened, and there may not even be a “what really happened.”

Oh, there’s definitely not. I firmly believe there’s no such thing as the truth, because we all have our different views of stuff. Certainly, the way I remember events from my childhood is not the way my best friend Nathan remembers events from our childhood, [which is] not the way my mom remembers an event from my childhood.

We never left Plato’s cave. We’re all manipulating shadows, dealing with shadows, remembering shadows. But that’s okay. I think that’s just the way we were made. But for me, writing the book, of course, was a way of holding on to Jerry, and a way of celebrating the life that we had together. But I gotta tell you, David—and you probably already know this—it’s so over. It’s so over. I mean, sure, I have the memories, and I have the gratitude. But my life now is all about Hal. It’s all about the next piece I’m going to learn on the piano, you know? I’ve very much moved along.

That’s good. I’m actually really happy for you. So many people end up mired in the past.

Yeah. And I could have been, and might have been, had things worked out differently. That’s the thing about Lawrence’s exhibit. It all opened this up again for me. Which had been pretty much put away. I tried to tell him that, you know, when he started asking me questions. I mean, this man is quite the researcher. Have you met him?

We’ve communicated through email a few times, but we haven’t actually met. We were supposed to have a phone call last March, when I first heard about the Jerry Hunt stuff. I was already on their press release list for other reasons. I emailed him right away, and we started going back and forth. And we were supposed to have a call and talk about it, but with my dumb call center job, it’s so hard to do any of that stuff. It was super strict. I was not allowed to have any kind of personal time whatsoever during the day. And it’s because it’s all through computers, they could watch everything that was happening. We had seven seconds in between phone calls when it was busy. I will say, one thing I’m thankful for is that when Covid hit, at least it was something I could do from home. It took them a little while, but eventually they sent us all home, to work from home. Whereas if I’d been working in a restaurant, for instance, that’s not something you can do from home.

Just be glad you’re not a truck driver. I think it may be quite as bad as being a roofer. Being a truck driver must be the absolute worst.

Brutal.

The way they monitor you, and how little they pay you, and how much you have to do when you’re not moving. And if you’re not moving, you’re not being paid.

Right. My last job was like that, but at least I was sitting still. I didn’t have to deal with gas prices, or accidents, or whatever reason you can’t hop out and deliver on time. I think it’s nuts that we refuse to treat people like humans. But that’s the capitalist system, and everything has to get wrung out.

The article that I read recently about truckers said that that’s the reason—really the reason—for all these recent protests about vaccination. It’s not that the vaccination issue in and of itself is so important, it’s that it’s the last straw. The truckers had already had it up to here. And then here comes the vaccination record.

Right. And I can understand that. Obviously, I fully support the vaccines, but I can understand hitting a point where you just can’t take any more. I mean, that’s why I quit the last job. I hit a point where I just couldn’t take it anymore. And I was like, “Alright, bye.” And I was lucky enough to land on my feet instead of flipping burgers at McDonald’s. It could have just as easily gone that way.

And it does go that way for a lot of people.

Oh, totally. But then I have to deal with the fact that I can’t get a job bagging groceries, for instance. I’ve been rejected from that job so many times in my life. Which I get, on a certain level, because they look at my resume, or they talk to me, and they just assume I’m gonna leave as soon as something better comes along.

Yeah.

But like, hello? It’s an entry level bagging job! This is not a career for anybody with what they pay you.

This is the crown jewel of the city. This is the Arboretum [Dallas Arborteum & Botanical Garden].

Oh, nice.

It is superb. You just can’t believe how nice it is, how large it is, and how many beautiful plants. It was originally the mansion of a man named DeGolyer, who was a petroleum engineer with SMU, and he left his home and his gardens to the city, and the city has just made a masterwork out of it. And this is a really popular time of year.

I’m sure. I can see all the cars. The place is packed.

You have to have reservations. There’s no way to go there without online reservations in advance.

That’s crazy.

And then here’s our lake, White Rock Lake, with a view of the city.

Is it a reservoir?

It was built to be a water reservoir. It isn’t used that way anymore. There’s the old pump station down there, which has been transformed into an event facility. Hal and I love to come over here and bike. We bike around the lake. But it’s very, very popular on the weekends.

I’m sure. I have the same trouble with trails around Durham. You can go during the week, and it’s okay. On the weekends, unless it’s freezing cold, they’re going to be slam-packed. So, if it’s freezing cold, I’m out there hiking in Duke Forest or whatever, but then as soon as it’s above the 40s, it’s just people everywhere.

We were here last Sunday. We came over to bike, but we didn’t bike around the lake. We did the Santa Fe Trail. And I’ll show you down here, it heads off to the left. And you can bike all the way to downtown Dallas, which is what we did. It runs along the creek, along the side of the creek. And then when you get back after your ride, you can have a good lunch at the Ale House, which is what we did.

That’s great. That’s a good day right there. My knee doesn’t like bike riding as much. I twisted my knee coming off Santa Fe Baldy, literally right off the summit, and then had to walk however many hours down that mountain. Which had been fine for a couple of years, but about a year ago I went for a ride from my house to Duke East Campus and back—just six or seven miles, no big deal—and I was limping for two days afterwards. It doesn’t hurt when I ride. I have good form. You know, my knees aren’t splayed out at weird angles or anything strange. And that was the third or fourth time that it happened. And I just started going back to acupuncture, hoping that I can get that back again, because I miss riding the bike, even if it’s just a little casual ride. I don’t need to do 100-mile rides anymore.

I couldn’t. But that Santa Fe Trail goes in that direction. The lot… this is all going to be torn down. It’s going to become a high-rise multi-use facility, which of course I hate to see, anyway.

There goes the neighborhood.

Yeah. But then again, that is the neighborhood. That’s what people want.

And things change, and they should change.

And it’ll fill up, and it’ll improve the store selection over here. And what they’re doing here with the roadwork is they’re fixing what was a very awkward intersection, and they’re going to make it better.

I think every intersection in this town is awkward. [Laughs].

It is awkward. It’s because people won’t stop. Because they won’t wait.

That thing where you’re getting off the highway, and the oncoming traffic is coming at you. I have questions.

Issues. [Laughs].

I’m never gonna get answers, but I definitely have some questions. But I’m really curious about when they started building interstates in the 50s. At some point, there was the first traffic jam. Wherever that was, it happened at some point. And somebody was like, “So this thing happened. And the way we’re going to make it better is by adding more lanes, so more people come out on the roads.” I understand that the car companies, for instance, stopped a lot of public transportation from being built. Raleigh, North Carolina had trolleys in the 1950s, and the car companies, paid the City Council to rip them out, to encourage more people to buy cars. And I like my Subaru, it’s very dependable. But I would also be quite happy if I could take public transportation 90% of the time.

I’m the kind of person that’s just made for public transportation, because I’m always in the middle of a book. And I would just love to be able to sit down and let the driving be done.

Obviously, I need something to transport the bass when I have music gigs. But, for instance, to get to work for me, it’s about three miles from my house. And I can cut, more or less, through town, so it’s like 15 minutes. It’s no big deal. But on public transportation, it’s an hour and a half. Because I gotta take one bus into downtown to the main station, and then wait, and then take the next bus out. And even though it’s not that far from the main station, it’s 25 stops on the bus line. And it’s definitely not an Express, you know? It’s a milk run that stops every three blocks.

Right. Yeah. Well, I went to college in Houston too. Of course, the thing about Houston, they were determined not to have public transportation for a long time, they just kept adding lanes, and kept expanding the roadways. And that’s the reason now that Houston has such a traffic problem. And it is probably the worst city in Texas for traffic. Austin is bad, but Houston is incredibly bad. Only recently, they’ve begun using public transportation. But you know what I’ve discovered? Uber! Uber’s wonderful. You meet people, and they usually know the area. It’s just it’s good experience. I’ve always had a good experience with Uber.

I just saw that, in New York City, they’re now listing taxi cabs in an app, so you can do either one now. Because there was a real problem. [The cab drivers] pay a fortune for those medallions and those licenses to drive, and then Uber comes along. And there was a problem with taxi drivers committing suicide in New York, because you’re taking away their livelihood, and they’re half a million dollars in debt for the license to begin with. And many of them are immigrants who are all working 25 jobs to take care of their families. It’s what my grandfather did when he was a young man, and his father, before the depression.

It’s a shift. It’s a cultural shift in a way. You know, where we’re learning to accommodate things like Airbnb and Uber. They’re “off the grid,” so to speak, and the people that are on the grid and that are committed to the grid are having to learn to adjust, and accommodation is necessary.

I think some of those things are great. Like when we first moved to Santa Fe, we had to wait a week and a half to get into our apartment. So, we just got an Airbnb for a week and a half in this lady’s house up on Bishop’s Lodge. And we had a nice time, and every now and again I’d see her around town, and she’s just this person I know and interact with. She was basically the first person I met in Santa Fe.

We’ve enjoyed Airbnb. Not only here, but in Europe, it works great.

Sometimes I do appreciate a hotel though. I’m not gonna lie.

Well, that’s true. Because they’re simpler.

Right? You don’t have to feel weird asking for more towels or whatever it is that you need.

The only bad experience we had was in Idaho one time where my sister’s family lives. There was no microwave. And I got in touch with the lady who rented it to us and said “Where is the microwave? We’ve looked everywhere!” She said, “Well, it’s not one of the amenities we offer.” And I said, “Well, it’s not an amenity, it’s a necessity!” [Laughs].

Yeah, at this point, basically.

That’s the only negative experience.

I travel with coffee stuff when I’m in the car. I have a pour-over, and I brought some coffee and I made good coffee for the people I was staying with this morning. I can deal without everything else in my life, but if I don’t have a decent cup of coffee in the morning, I will absolutely kill everybody.

I hear you, David. That’s one thing—that’s maybe the thing. That, and one Diet Coke a day. But that coffee is very important to me. And I read recently, and I do believe this, that the best coffee is the pour-over that you do slowly.

That’s what I usually do.

That’s the best coffee. That’s better than any maker they’ve created. And it’s simple.

And it’s been around forever. I have a Chemex, and Chemex was invented in 1940. It’s in the Museum of Modern Art, in their Industrial Design collection. And it’s great. I thought for a long time it was gonna be really complicated. And then when I started baking, our coffee company showed me how to do it, and I was like “What? It’s this easy?” I do it on a scale, but for years, I didn’t have a scale. I just did it by volume, with a Pyrex measuring cup.

This is the magnificent Swiss Avenue, where we rented the house for ten years, all through the 70s. There were these wonderful, grand homes, and the tree-lined streets, and the grassy mediums. It was just paradise living here. And it’s still paradise, if the time is right in your life to maintain a hunk of property like this.

It’s a beautiful street. These trees. Oh, I love the Crepe Myrtles in your yard, by the way.

Oh, I’ll tell Hal.

Crepe Myrtles are funny to me because I don’t really feel one way or the other about the flowers and the leaves. But I love the trunks. And the wood is just so beautiful. And it feels good to touch.

The trunks are almost human, almost like tissue or muscle.

Yeah, very much so, maybe because they’re almost naked since they don’t have the thick bark like the oaks and everything else.

And they can take the heat, and they can take the drought, and they’re reliable. So, this was the house we rented. This brown house.

[Sees dog] Oh, look at that little guy.

Is that a Yorkie? Yorkshire Terrier?

Yeah, maybe. I’m kind of bad with my breed names sometimes. There’s like 10 that I can do really well; the rest of them, I have absolutely no clue. No wonder you guys liked this house. It’s huge.

We should back up a little bit if you take that picture, because you’ll see Jerry’s studio.

In the back there?

Uh-huh. That’s a garage apartment. And that’s where he and Houston Higgins set up their studio.

When Jerry was working, would he talk about his stuff with you, or would you just show up at the performance like everybody else and be surprised? I’m always curious about how people work.

I never understood what Jerry did…

That’s not surprising…

…and I never much liked it.

Oh, really?

The only thing of his that I really liked was Song Drapes.

Oh, interesting.

And I don’t know why. Maybe because of the association with Karen Finley. But he got into what I would consider more “musical” music. [Laughs].

Oh, no, that makes total sense. Because his stuff is not “music,” in the traditional sense.

And I am traditional. I’m a very traditional person about music and about a lot of things. But Jerry, one thing he did say, you know—and I think I might have put this in my book—he said “I have learned not to mention anything to Stephen about what I do, or even to play a tune that I’ve written, because if he likes it, I know it’s the kiss of death!” [Laughs].

That’s hilarious. I have this theory that companies should hire me to look at their products. And if I like it, they shouldn’t make it, because it’s just not going to sell well if I’m into it.

Well, it was really funny. So he did his thing, and he was off making these odd sounds, or he was at the piano doing this incredible stuff, when I really wanted him to play Brahms. But he did it, and then, of course I went to concerts and I traveled with him. We made a lot of trips together when he would give concerts in different places. And I would sit there, and I would just…I just couldn’t believe…

Like, “Oh my God, I share my bed with this man?”

Yeah! And yet, I felt it. I felt the intensity. I mean, the people that were there, the way they were responding, I picked up on that. And it really got me worked up.

I think that’s what really attracts me about Jerry’s work is that there’s something there, and it’s really obvious that there’s an energy transference happening. If he was just screwing off, you could tell, and it’s really obvious that it is not that.

Well, very often, at the end of it I would feel transformed, but chastened in some way. Or redirected. Maybe redirected is a better word.

I think that’s really important. Something I look for in music, and something I certainly hope that people get from my performances, is that they get moved. Maybe not far; it might just be an inch or whatever. But you need to be in a different place from where we started. And if you’re not, then I failed.

Well, that’s how I feel about most experiences I have with art, and music, and films, for sure. I don’t want to come out the way I was when I went in.

Right.

And I never did with Jerry. And there was another element too, David, that I was almost like his mother. When he performed, I wanted him to do well. And I wanted everybody to like it. And I wanted it to be a positive experience for him. And I could see that the people who came—

sometimes there weren’t many of them—they were very much affected by what he did. And that made me really pleased for him, and happy for him.

I feel like it’s the kind of thing that as long as you don’t leave in the first ten minutes, you’re going to be a different person at the end of it.

And many do [leave]. Many people walked out. And I hated to see that. I always felt so bad when I saw that.

A lot of people can’t open themselves up to new ideas, regardless of what that idea is, whether it’s religious, or musical, or political or whatever. I feel like a lot of people build walls. And that’s how they contain themselves. And if you try to remove a brick from that wall, sometimes they react really well to it, and sometimes they’ll rip your head off.

Sometimes people are just not in that place in their life. Or it’s not the right time. They’re not available, and you have to just give people the benefit of the doubt. But when I would sit in Jerry’s audiences, I didn’t want anybody to leave. I wanted everybody to, you know, just like I said…I was like a mother. I wanted that recital to go good.

I always actually kind of take it as a positive sign that people leave, because you’ve moved that person, maybe even in a negative way.

Yeah.

But they came, they took the time, maybe they spent the money to come in, and you moved them so much that they literally got up and left.

That’s a very good way to look at it.

And that counts. If I listened to something, and I truly hate it, I’m really intrigued, because that got an emotional reaction from me. And a lot of stuff doesn’t move me, you know? I’m just neutral on it. I don’t hate things, because there’s no use in really hating things. So, if you can make me hate something to the point that I want to get up and leave, then my butt’s sitting in that chair for another hour to see what I can learn from it.

Well, like you said, the worst reaction is the reaction where you just begin paging through the program.

Oh, yeah.

And I see that at the Symphony. I go fairly regularly to the Dallas Symphony, and there are a few people from time to time that, even in the most beautiful or most intense moments, they’ll pick up the program and start leafing through and I’m thinking “What’s happening?”

People are so funny, and it’s hilarious, too, you know, that that happens with Brahms, it’s not just like weird 20th century stuff. That happens during Mozart. And whatever, Mozart’s not everybody’s cup of tea, and that’s fine. Honestly, I can’t remember the last time I pressed play on a Mozart album. But if I’m at the symphony, I would also be totally happy to hear a Mozart symphony.

We’re headed back now. We’ve had our little tour. We’re gonna go back a different way, for the variety of it. We lost our good cafeteria. That’s one of the sad things about the pandemic. You know, as a vegetarian, I’ve always appreciated cafeterias.

I’m also a vegetarian.

They’ve gone now. They’re just too risky. People are afraid of buffets.